TCM has made an commendable effort to bring silent film comedy shorts to television. The channel aired 87 newly restored Mack Sennett comedies last September and followed this up in May with a 12-hour tribute to Harold Lloyd, which included a number of early one-reel rarities. These marathons allowed me to view many films that were previously unavailable to me. It made me feel like a paleontologist let loose in a new excavation site.

My book The Funny Parts was designed to provide film comedy enthusiasts with a means to travel through the history of film comedy and see the way in which gags and routines were developed. What made writing this book difficult at times was the fact that the film record is imperfect. Gaps exist that sometimes made it problematic to identify the fine graduations in a routine's evolution. This, in many ways, made my work on The Funny Parts just as tricky as the job that a paleontologist undertakes to reconstruct a fossil skeleton. Even when they are in possession of a complete skeleton, paleontologists are often unsure what to make of the various parts. You cannot connect the hip bone to the thigh bone until you can first figure out which bone is which. Paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope reconstructed an Elasmosaurus skeleton with the head on the wrong end. When reassembling an Iguanodon skeleton, Gideon Mantell placed a thumb spike at the end of the animal's snout. Thomas Jefferson once came into possession of prehistoric bones and, upon examining the long limb pieces and the large claws, he came to the conclusion that the bones belonged to a giant prehistoric cat. Wrong. The bones belonged to a giant ground sloth.

Henry Fairfield Osborn, a major authority in the field of paleontology, determined that a fossil tooth belonged to the first anthropoid ape when it, in fact, belonged to a peccary, which is an ancient pig. Mistakes are made, but they are understandable and acceptable. Speculation, wrong or right, is a crucial part of the identification process.

The development of film comedy was dynamic during the silent era. It was in a continual state of motion. Routines passed down the line from one comedian to the next in free succession. I was not always aware of every link in the chain when I wrote The Funny Parts. Take, for example, Buster Keaton's changing room scene in The Cameraman (1928). I analyzed that scene in The Funny Parts without being aware that one of the writers on The Cameraman had previously used the idea of a man changing clothes in a cramped space in the 1927 feature Horse Shoes (Monty Banks has to change into pajamas in a berth). I elaborated on the Banks routine in my next book, Eighteen Comedians of Silent Film, as a way to integrate it into the comedy routine flow chart. I am relieved to say that the belated discovery of the Horse Shoes routine did not upset my original analysis of the routine. This is partly due to Keaton, who could make a routine his own regardless of what had been done before. It may be that, sometimes, the history of a routine is not so much a chain as it is a tapestry.

Theatergoers must have experienced a great deal of déjà vu in the days of silent film comedy. Charley Chase appeared in Publicity Pays (1924) scaling a high-rise hotel in pursuit of a monkey. Three weeks later, Dorothy Devore was on theater screens chasing a monkey across a skyscraper ledge in Hold Your Breath (1924). A rush hour scene in Fred Fishbach's Hurry Up (1922) was likely still in the recent memory of theatergoers when a similar rush hour scene turned up in Harold Lloyd's Safety Last! (1923). Gags and routines were easily shared and sometimes traded back and forth. A comedian chasing a monkey across the facade of a tall building may be the sort of idea that two writers in two separate places could get at roughly the same time. This "great minds think alike" concept, also known as parallel thinking, has been known to happen. But I suspect that an earlier version of this scene from an unknown source was the inspiration for both instances of monkey business. Harry Sweet may have climbed a building to retrieve a monkey in a Century comedy. Charles Dorety may have found himself on a ledge with a monkey in a Sunshine comedy. It is always possible that a long-lost comedy will suddenly turn up to reveal this and other intriguing content.

As part of my research for The Funny Parts, I opened up a blank pad in my lap and settled back to watch a collection of Keystone comedies. Mack Sennett produced the Keystone comedies from 1912 to 1917, after which he left the company to form the Mack Sennett Comedies Corporation. The Keystone comedies reflect a relatively dull and narrow stage in the early development of film comedy. This became clear to me during my viewing session, which turned out to be somewhat of a disappointment. When the films were over, my pad remained blank. I had failed to identify anything that even vaguely resembled a gag or a routine. These films, which were designed as mock melodramas, simply allowed actors to make funny faces, race around rooms, fall down, and hit one another. Gags and routines were not part of the formula.

I prefer the type of wildly exaggerated gags and routines that the Sennett crew produced in the 1920s. Let me provide, as an example, a scene from Wall Street Blues (1924). Billy Bevan does not notice that he is dripping cleaning fluid onto a small dog. A dapper gentlemen lights a cigarette and tosses the match in the direction of the chemical-soaked dog, which proceeds to vanish instantly in a puff of smoke. Nothing is left of the creature except its doggie sweater. Bevan assumes the missing little dog was eaten by a big dog standing nearby and licking its lips. To avoid upsetting the woman who owns the dog, Bevan steals a toy dog from a little boy, wraps it up in the sweater, and fastens it to the end of the woman's leash. The woman, unaware of the dog's death or Bevan's deception, casually walks off dragging the toy dog at the end of the leash. This is great, crazy stuff. It is not the type of routine that you will ever see in a Keystone comedy.

To understand the primitiveness of the Keystone comedies, one need only set the Keystone comedy A Bird's a Bird (1915) against comparable comedies made by Sennett and Roach in the following decade. A Bird's a Bird starts with Mr. Walrus (Chester Conklin) learning that his in-laws are coming over for dinner. He doesn't have anything to serve them, which leads him to steal a cooked turkey from his neighbor's kitchen. A parrot is loose in the room as Conklin prepares to serve the pilfered bird. I was expecting something like this to happen.

This scene appears in the Three Stooges' Crash Goes the Hash (1944), but the routine in fact turned up much earlier in a 1925 Sennett comedy called Cold Turkey (1925). This became a familiar comic equation - parrot + turkey = shenanigans. I had seen the routine played out so many times before that it was, in my mind, inevitable. But, no, the idea of a parrot moving around inside of a turkey and making dinner guests believe they were under attack by a zombie gobbler was comic business for another day. Nothing as inspired and fantastic as that ever occurs in a Keystone comedy. Conklin becomes worried when the neighbor (Slim Summerville) joins him for dinner. Will the neighbor realize that the turkey being served is the turkey from his own home? Will he become enraged and attack Mr. Walrus? It doesn't matter as, at some point, a despicable "foreigner" (Hank Mann) shows up and plants a bomb in the turkey. The neighbor learning that Conklin stole his turkey loses importance when the audience is waiting for a bomb to explode.

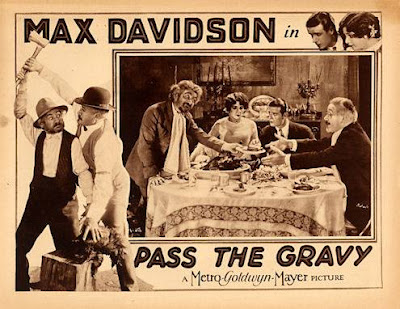

The same dilemma, sans the bomb, befell Max Davidson in Pass the Gravy (1928). Unlike Conklin, Davidson hadn't been the one to steal the bird (a prize-winning rooster this time instead of a run-of-the-mill turkey). Davidson's son (Spec O'Donnell) stole the rooster so that he could pocket the money that his father gave him to pay the butcher. The film builds suspense as the viewer waits for the neighbor to notice a "1st Prize" tag on the rooster's leg and realize that the cooked bird that he has been served is, in fact, the champion rooster stolen from his yard. This is early cringe comedy. Max's daughter and the daughter's boyfriend do their best to retrieve the chicken leg from the neighbor's plate before he has time to discover the tag. Their efforts soon turn into a madcap game of football. This excellent comedy is vastly more sophisticated and refined than A Bird's a Bird.

The TCM marathon did reveal that, late in the history of Keystone, gags and routines did begin to emerge. A standard silent comedy routine in which a comedian poses as a mannequin is discussed at length in The Funny Parts. The idea of a comedian pretending to be an inanimate object was unsuitable to Keystone's violent, fast-paced style, but the makers of Keystone's The Surf Girl (1916) were able to figure out a way to speed up the action and subject the comedy protagonist to a slapstick drubbing. The scene starts out with Raymond Griffith eluding an irate man by hiding out in an arcade. He comes across a game in which the players knock hats off mannequins' heads by pitching balls as the mannequins rush past on a treadmill. Griffith, determined to stay out of the clutches of the irate man, struggles to pose as a mannequin while being pelted by balls. It's a perfect adaptation. The treadmill has been added to provide the speed and the balls have been added to provide the bruises.

Dizzy Heights and Daring Hearts (1915) includes an early version of another routine that I wrote about in The Funny Parts. Interestingly, this is not an embryonic version of the routine. It is, in fact, more carefully developed than later versions. Chester Conklin pretends to be the bootblack to make contact with a shapely woman sitting at a bootblack stand with a newspaper unfolded in front of her face. Conklin no sooner slips off the woman's shoe then he becomes startled to notice a big black toe peeking out of a hole in the woman's stocking. Conklin pulls the newspaper down from the woman's face and, once her face is in view, he is left without a doubt that the woman's skin is dark from toe to head. Conklin flees in panic as the actual bootblack laughs uproariously.

This routine was repeated for years in various permutations. To my knowledge, the earliest version can be found in a 1909 Essanay comedy called Mr. Flip. The film's plot is entirely built around this one gag. A soubrette receives an invitation to meet an amorous fan (Ben Turpin) for dinner. As a joke, the soubrette conceals her black maid's face behind a veil and sends her to meet the man in her place. Turpin is passionately embracing his date when he disarranges her veil and reveals her true identity. The sight of an interracial couple causes a great scene and Turpin is roughly ejected from the restaurant.

Here are two distinctly different versions of the routine.

Larry Semon in Frauds and Frenzies (1918)

Buster Keaton in Seven Chances (1925)

The routine is played out again by Semon's partner, Stan Laurel. Laurel's reaction to the black woman is no less subtle. He screams and runs away as if his life depended on it.

The message of this routine could not be more clear. The races must not mix. The caption of this lobby card puts it another way.

An individual must "[draw] the color line." It could be argued that today's politically correct Hollywood has gone to the opposite extreme, promoting interracial couples at every opportunity.

Here is a version of the routine that leaves out the issue of race.

My favorite discovery among TCM's Sennett comedies was a 1915 Keystone release called A Lover's Lost Control, in which Sydney Chaplin runs amok in a department store. Chaplin turned out the most imaginative, subversive and ultimately funniest comedies in Keystone's history. Funny business occurs in A Lover's Lost Control when Chaplin, who is in the midst of imposing his lecherous wiles on a pretty young woman, mistakes a mannequin's leg for the woman's leg. Chaplin used the gag again in a Standard Film Corporation feature, Bombardiers (1919). This time, the comedian finds a mannequin's leg in his lap and cheerfully assumes that the leg belongs to an attractive woman sitting beside him. The routine was further refined in the coming years by Charley Chase and Harry Langdon. The development of the routine is laid out well in an article by David Kalat. Langdon continued to make use of this routine for the remainder of his career.

Defective Detective (1944)

Abbott & Costello revived the routine for a 1954 episode of The Colgate Comedy Hour.

Keystone's humor started to expand to more imaginative and spectacular proportions by 1915. In Dizzy Heights and Daring Hearts (1915), Chester Conklin spins around on an airplane propeller as the airplane soars across the sky. In The Surf Girl (1916), Raymond Griffith and Fritz Schade have a rousing fistfight while standing atop a moving Ferris wheel.

The earliest comedy of the Lloyd marathon was Lonesome Luke, Messenger (1917). Already, you can see the comedian playing with classic stage routines. Lloyd escapes from a pursuer by diving down a chute, which is a gag straight out of the English music hall. Later, Lloyd takes a break from being chased by Snub Pollard and Bud Jamison to render another well-established stage routine. The action begins with Lloyd slipping behind a curtain to hide. Pollard and Jamison, puzzled by Lloyd's sudden disappearance, mill about with their backs to the curtain. Lloyd, unable to resist an opportunity for mischief, pops out of hiding just long enough to poke at his pursuers. The men, who can see no one else around, blame each other for the pokes and get into a heated argument with one another. It's a simple bit of business and yet it is guaranteed to make an audience laugh.

The highlight of The Marathon (1919) is Lloyd's execution of the famous "mirror routine" opposite Eddie Borden. Setting this routine apart from the later versions is its slapstick climax. As Borden leans forward to get a closer look at his dubious reflection, Lloyd leans forward in precise synchronization, causing the two men to precisely slam their heads together. This forceful collision leaves Borden dazed and Lloyd riled. Lloyd waits until Borden is not looking to shove him, smack him, and break a vase over his head. The mirror routine is so clever and charming that the violence is unnecessary. It is a surprising flaw in an otherwise skillful rendition of the routine. Lloyd, an astute comedy maker, was working at the time to civilize his "glasses" character and move away from crude physical violence. It isn't reasonable for him to have resorted to this sort of action when he didn't have to. But the routine doesn't end there. After Lloyd has beaten up Borden, a woman (Dorothea Wolbert) comes along and continues the routine with Lloyd. This creates a rare mixed-gender variation of the routine.

In Take a Chance (1918), Lloyd rolls down a hill trapped inside of a trash can. A police officer runs frantically down the hill to keep ahead of the speedily rolling trash can, which threatens at any moment to crush him. The scene brings to mind Buster Keaton running down a hill to avoid rolling boulders in Seven Chances (1925). Of course, the Seven Chances scene is much more elaborate, but both scenes make use of the same basic idea.

A couple of the gags used in Next Aisle (1919) were recycled from other films. A revolving door routine is reminiscent of a revolving door routine in Chaplin's The Cure (1917). Another gag, which opens the film, was used the year before by Buster Keaton in The Bell Boy. It's a simple gag. A window cleaner is using a rag to scrub a storefront window clean. Suddenly, the man steps freely through the window frame, revealing that the frame lacks a glass pane and the window cleaner's efforts were nothing more than a playful (or demented) pantomime. A number of comedians performed this gag through the years.

Buster Keaton in The Bell Boy (1918)

Roscoe Arbuckle in The Garage (1920)

Stan Laurel in Short Orders (1923)

Next Aisle includes other notable routines. Lloyd manages a faithful rendition of the Commedia dell’Arte routine “Lazzi of the Statue” when he pretends to be a mannequin in a department store's display window. One clever routine that is new to me involves Lloyd, an eager shoe salesman, driving a customer across the room as he struggles to squeeze a shoe onto his foot.

This collection of Harold Lloyd films were put together by the Harold Lloyd Trust under the direction of Lloyd's granddaughter, Suzanne Lloyd Hayes. Hayes said that she was careful in selecting the early comedies to be restored for this tribute. She explained that she passed on restoring many of the early comedies because they were weak on story and characterization. It was not surprising to hear Hayes say that the rejected films offered nothing more than actors running, hitting each other, and falling down. That's where Lloyd had to start before he refined his craft and became one of the greatest comedy artists in film history. Coming to an appreciation of the fascinating twists and turns that occur in an artist's evolution is what makes film study worthwhile.

Safety note in regards to Billy Bevan's combustible dog

A modern audience might not fully appreciate this joke. Cleaning fluids were notoriously flammable in the 1920s. It wasn't until after World War II that these products were reformulated to make them safer. That is not to say that the cleaning fluids of today cannot cause a fire. They remain flammable due to a number of ingredients, including isopropyl alcohol and monoethanolamine. So, do not allow cleaning fluids to make contact with a flame. Keep yourself, your family and your pets safe. This is a public service message from the National Fire Protection Association. And me, Freddy the Fire Extinguisher.

More Sennett clips

The Three Stooges Reprise the Parrot-Inside-a-Turkey Routine

G. I. Wanna Go Home (1946)

Three Dark Horses (1952)

Mirrors play crucial roles in a number of Harold Lloyd comedies

One Last Thought

Harold Lloyd was still settling into his "glasses" character at the start of 1918. Look Pleasant, Please (1918), which was included in the TCM marathon, showcases the comedian during this period. The film offers little in the way of story and characterization. Lloyd stumbles into a new job as a photographer and proceeds to make a mess of things. Slapstick violence dominates the film as the still below suggests.

Lloyd went far from this film to Bumping into Broadway and From Hand to Mouth, which are two films that he made at the end of 1919.

Silent film comedy went through a major transition in 1918 and 1919. During this period, many artists and businesmen helped to pave the way to film comedy's golden age of the 1920s. But it is the contributions of four men that stand out sharply in my mind.

1.) Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin continued his previous efforts to advance characterization and storytelling with A Dog's Life (1918) and Shoulder Arms (1918).

2.) William Fox. As the head of the Fox Film Corporation, Fox invested an extraordinary amount of money into his ambitious Sunshine comedy series. The series set a new standard, expanding the scope of film comedy. Suddenly, producers were under pressure to assure that a comedy film displayed elaborate staging, fantastic special effects, and spectacular stunts.

3.) Larry Semon. This former newspaper cartoonist filled his films with gags that were fast and furious. The gag was king in Semon's comedies, which no doubt had an influence on his peers.

4.) Harold Lloyd. Lloyd followed Chaplin's example in advancing story and characterization, but he also demonstrated incomparable care and finesse when it came to crafting routines.

It was due to these men and others that classic film comedy of the 1920s came to be defined by outrageous gags, well-designed routines, big-budget action, sympathetic characters, and comprehensible stories.

.png)

_01.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment